Mat Collishaw

Lakeside Arts, Nottingham

At times haunting, theatrical and hypnotic, Mat Collishaw’s solo show at Lakeside Arts is a visual spectacular. Yet behind the smoke and mirrors, at the heart of each work is an underlying sense of loss, desperation, and disillusionment.

This retrospective exhibition is a homecoming for the Nottingham-born artist, who rose to prominence in the 1990s as one of the ‘young British artists’. The show’s centrepiece, Albion (2017), is a large-scale installation depicting an almost life-sized version of the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, digitally rendered through a laser scan. The projected image reflects across a periscope arrangement of angled mirrors, and eventually lands on transparent film, as if floating in the gallery space. The installation uses a technique borrowed from Victorian theatre to create eerie apparitions, and The Major Oak itself appears like a shackled ghost – its decaying branches propped up by crutches. Made at the time of the EU referendum, Collishaw uses the Major Oak as a metaphor for the preservation of an idealised Britain – the romance of a time now long gone.

![]()

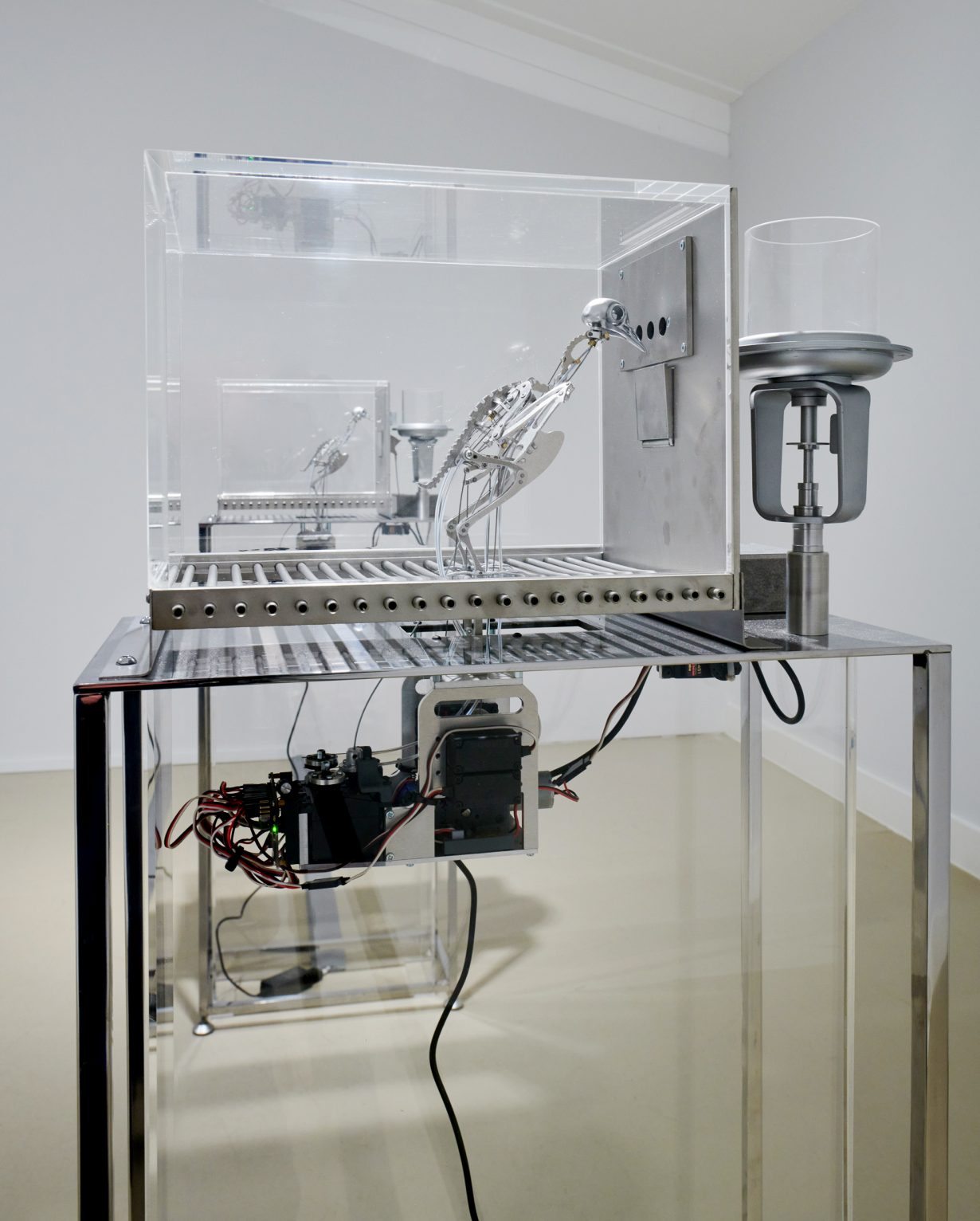

Contemporary technologies evoking past eras is a signature of Collishaw’s work. The Machine Zone (2019) is an installation of robotic birds, each contained within a transparent box, which references the behavioural psychologist BF Skinner’s experiment of the 1940s, in which the behaviour of small animals was conditioned by a random reward system. The findings, that confusion breeds addiction, is the psychology behind social media; the gratifying ‘pings’ of notifications taps into something primal. Despite the lifelike movement of the birds, Collishaw allows the electronics to be seen, as if exposing the manipulation underlying how we communicate with each other, adding a darker sense to the word ‘Twitter’.

Also exploring the roots behind our interactions and self-display, The Centrifugal Soul (2016) is a contemporary interpretation of a zoetrope – a large three-dimensional sculpture which rotates rapidly under strobe lighting to animate its otherwise static elements, and which creates a seductive performance of birds fanning their feathers. Drawing comparisons with human behaviour – from social media selfies to the consumption of flashy designer goods – the flaunting of appearances is presented as essential to continuing the species, but the repetitive cycle of mating rituals appears as an act of desperation.

![]()

Evoking vanitas paintings through a rich palette and chiaroscuro lighting, Collishaw’s photographic series Last Meal of Death Row, Texas(2010) recreates the final meals requested by prisoners before execution. The fragility of life and the insignificance of earthly pleasures was allegorical in the still lifes of Dutch masters. But here, the bowls of cereal and fast-food containers signal the hard reality of a person’s imminent demise. In Camera (2015) similarly presents charged images shrouded in mystery: crime scene negatives from the 1930s and 40s – including upturned homes, a cubical toilet, and hanging meat. The installation comprises twelve photographs, each mounted in transparent vitrines. In the dimly-lit gallery the phosphorescent ink photographs are invisible, but a series of blinding flashes across the installation briefly reveals a crisp image, which lingers then fades in an eerie glow – evoking the flash-photography of early forensic photography. Encountering the work is an unsettling experience; much like being the detective arriving on the scene, the illicit encounter is unknown, and even innocuous images are tainted.

In referencing the technologies behind image-making – from the photographer’s flash to theatre sets and zoetropes – Collishaw is like the magician revealing his secrets, signalling that our worldly beliefs might be acts of misdirection, concealing darker meanings. Thinking about the show’s lifespan – from March 2020 to now – and our changed relationships to digital communication, rituals of courtship, or even remembering the optimistic slogans of Brexit before the present relentless circus of uncertainty, I wonder if the returning audience might already be more distrusting of appearances. Either way, the exhibition is both visually captivating and a thought-provoking reflection on our existence.

Mat Collishaw is at Lakeside Arts, Nottingham, Tuesday 18 May – Sunday 5 September

This retrospective exhibition is a homecoming for the Nottingham-born artist, who rose to prominence in the 1990s as one of the ‘young British artists’. The show’s centrepiece, Albion (2017), is a large-scale installation depicting an almost life-sized version of the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, digitally rendered through a laser scan. The projected image reflects across a periscope arrangement of angled mirrors, and eventually lands on transparent film, as if floating in the gallery space. The installation uses a technique borrowed from Victorian theatre to create eerie apparitions, and The Major Oak itself appears like a shackled ghost – its decaying branches propped up by crutches. Made at the time of the EU referendum, Collishaw uses the Major Oak as a metaphor for the preservation of an idealised Britain – the romance of a time now long gone.

The Machine Zone, 2019, installation view. Courtesy the artist

Contemporary technologies evoking past eras is a signature of Collishaw’s work. The Machine Zone (2019) is an installation of robotic birds, each contained within a transparent box, which references the behavioural psychologist BF Skinner’s experiment of the 1940s, in which the behaviour of small animals was conditioned by a random reward system. The findings, that confusion breeds addiction, is the psychology behind social media; the gratifying ‘pings’ of notifications taps into something primal. Despite the lifelike movement of the birds, Collishaw allows the electronics to be seen, as if exposing the manipulation underlying how we communicate with each other, adding a darker sense to the word ‘Twitter’.

Also exploring the roots behind our interactions and self-display, The Centrifugal Soul (2016) is a contemporary interpretation of a zoetrope – a large three-dimensional sculpture which rotates rapidly under strobe lighting to animate its otherwise static elements, and which creates a seductive performance of birds fanning their feathers. Drawing comparisons with human behaviour – from social media selfies to the consumption of flashy designer goods – the flaunting of appearances is presented as essential to continuing the species, but the repetitive cycle of mating rituals appears as an act of desperation.

The Centrifugal Soul, 2016. Courtesy the artist

Evoking vanitas paintings through a rich palette and chiaroscuro lighting, Collishaw’s photographic series Last Meal of Death Row, Texas(2010) recreates the final meals requested by prisoners before execution. The fragility of life and the insignificance of earthly pleasures was allegorical in the still lifes of Dutch masters. But here, the bowls of cereal and fast-food containers signal the hard reality of a person’s imminent demise. In Camera (2015) similarly presents charged images shrouded in mystery: crime scene negatives from the 1930s and 40s – including upturned homes, a cubical toilet, and hanging meat. The installation comprises twelve photographs, each mounted in transparent vitrines. In the dimly-lit gallery the phosphorescent ink photographs are invisible, but a series of blinding flashes across the installation briefly reveals a crisp image, which lingers then fades in an eerie glow – evoking the flash-photography of early forensic photography. Encountering the work is an unsettling experience; much like being the detective arriving on the scene, the illicit encounter is unknown, and even innocuous images are tainted.

In referencing the technologies behind image-making – from the photographer’s flash to theatre sets and zoetropes – Collishaw is like the magician revealing his secrets, signalling that our worldly beliefs might be acts of misdirection, concealing darker meanings. Thinking about the show’s lifespan – from March 2020 to now – and our changed relationships to digital communication, rituals of courtship, or even remembering the optimistic slogans of Brexit before the present relentless circus of uncertainty, I wonder if the returning audience might already be more distrusting of appearances. Either way, the exhibition is both visually captivating and a thought-provoking reflection on our existence.

Mat Collishaw is at Lakeside Arts, Nottingham, Tuesday 18 May – Sunday 5 September

21 May 2021